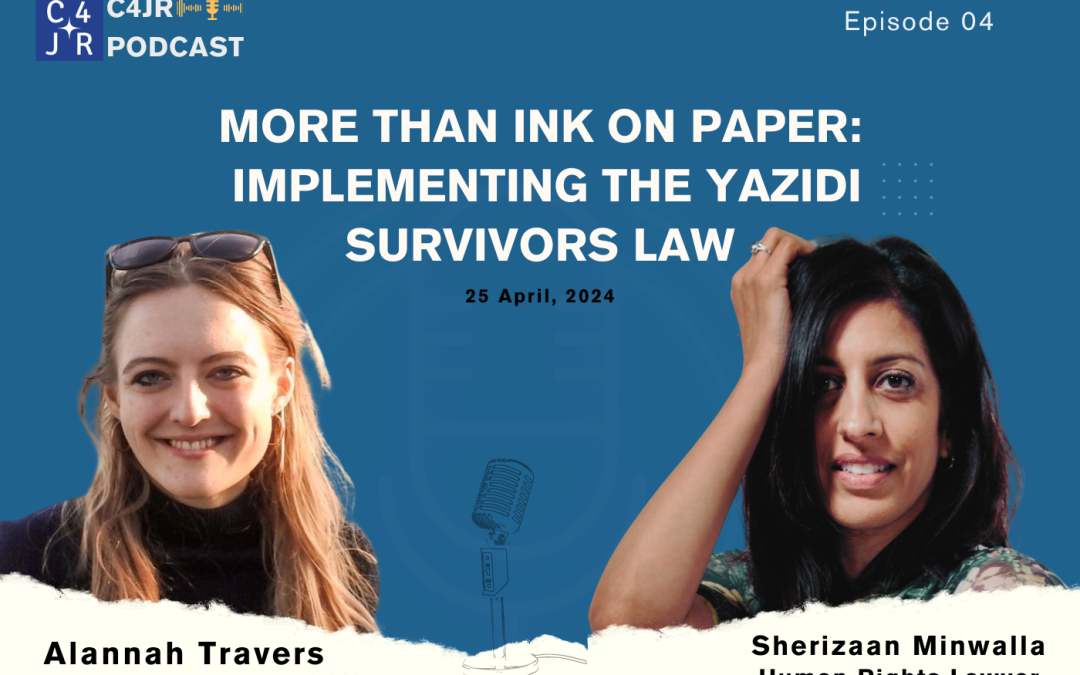

Implementing the Yazidi Survivors Law: Listen to C4JR in conversation with Sherizaan Minwalla here.

Episode Description:

Sherizaan Minwalla is a renowned human rights lawyer based in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and founder of Taboo LLC, a pioneering human rights and justice consulting practice. With a wealth of experience advocating for refugees, asylum seekers, and survivors of gender-based violence, Sherizaan’s work has a special focus on ensuring survivor-centered principles and practices.

In this episode, C4JR’s Alannah Travers spoke with Sherizaan about her efforts to advocate for ethical engagement and the protection of survivors’ rights in media reporting and legal processes, including her own groundbreaking research. Offering invaluable insights into the complexities of transitional justice and accountability in Iraq, Sherizaan also shared her reflections on the 2021 Yazidi Survivors Law (YSL), shedding light on the challenges and progress made in delivering long-awaited reparations and securing justice for survivors of ISIS conflict and sexual violence. Don’t miss this enlightening conversation with Sherizaan, as we strive to amplify voices of justice and uphold the rights of survivors.

This conversation was recorded in April 2024.

Introduction:

Transcript:

Alannah Travers: Welcome to C4JR’s podcast series, “More Than Ink on Paper: Implementing the Yazidi Survivors Law”, where we platform relevant voices around the YSL, as it is known, which has too often also been referred to as “ink on paper” by some survivors of ISIS crimes to voice their doubts about the government’s commitment to delivering long-awaited reparations guaranteed under the legislation. We’ll be speaking to those working to ensure that this is not the case, and take a sweeping look at issues of transitional justice and accountability in Iraq, through the process of seeking to implement the law.

Today, we are delighted to be joined by Sherizaan Minwalla, a human rights lawyer based in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, and Founder of Taboo LLC, a human rights and justice consulting practice. Sherizaan has represented refugees, asylum seekers and immigrant survivors of gender-based violence to achieve legal protection in America, and for over a decade has addressed women’s rights and the rule of law in Iraq, including with IOM Iraq to advocate that Do No Harm and survivor-centred principles and practices were applied to the Yazidi Survivors Law, and in developments since 2021. Sherizaan has also co-authored fantastic research on how survivors of ISIS conflict and sexual violence specifically have perceived journalistic practices as media have reported on atrocities they suffered in captivity, and Sherizaan has also conducted training on such ethical engagement for C4JR-members, too. Thank you for joining us.

Questions:

Alannah: Sherizaan, you are a US-qualified lawyer with more than 10 years of living and working in Iraq. Can you tell us more about how it came to be that Iraq became your home?

Sherizaan Minwalla: Thank you so much for having me. I first came to Iraq back in 2005. I was practising immigration law in Chicago, and I was representing survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault from countries all over the world. After the war started, my colleague came to Iraq and set up a program to address mental health issues for survivors of torture and family members who were affected by torture, which was widespread in Iraq. I was just very interested, of course in the Middle East, but also in how communities responded to issues of violence against women and girls. I started travelling here, but then I moved here in 2007 as the country director for Heartland Alliance. I was working for the National Immigrant Justice Center in Chicago, which was a program of Heartland Alliance.

Once I came to Iraq, I spent the next four years running their human rights programs, and I started the legal protection program, where we set up a framework for responding to and advocating for the rights of individuals in the criminal justice system and in the personal status courts; for individuals who had faced gender-based violence, specifically, as well as human trafficking. So that’s how I started, and then I’ve left and come back with different organizations over the last few years, and here I am.

Alannah: You’re really a pioneer through all this different experience in seeking to highlight and mitigate quite a lot of the harmful practices of journalists, but also others, who have interviewed survivors, highlighting the false hopes and expectations that may have been played upon in order to secure their testimony. I thought it made sense to open our conversation with this because I really encourage listeners to seek out some of your work, and I’ll link them in the show notes. Could you reflect on some of these practices and the important lessons as we approach the tenth anniversary of the Yazidi Genocide and consider how things have changed (or not!) in terms of journalistic reporting, and what support is out there to empower survivors?

Sherizaan: Yes, absolutely. Thank you. One of the things that really struck me when I first came here and started working on these issues, was how much women and girls self-regulated in order to maintain their reputation and honour and live within the social codes of the culture. Some of the women and girls whom I came across were living in the shelters for protection; if someone was missing from their home for one night, this would raise all sorts of problems and potentially put them at risk of being killed for losing their honour. So, this was the culture and the context in which the ISIS attacks and genocide against the Yazidi community happened.

I distinctly remember the first time I saw a Yazidi woman on TV in the early days, in August 2014, talking about escaping from ISIS and then returning to the Kurdistan Region and talking about how she had not faced sexual violence, but she was aware of other girls who had. And the first thing that I thought was, how is she going to be okay? Because I know the culture and I know that this can really be a problem for people in terms of stigma and shame, and all of these issues that already existed in the culture. So, soon after, a number of people who were taken captive started to escape, that was especially in 2014 and 2015, and many of them fled and came to the Kurdistan Region, and then many of them went into the camps. There were many camps, there still are many camps, where Yazidis who were displaced are living. I started to notice that all of these journalists were coming and going to the camps and I started seeing the articles and the interviews that were published specifically focusing on the topic of sexual violence.

I just knew that there were so many issues with what was happening. So, for example, if you continue to interview someone over and over again, that this can be very traumatic. If you expose someone’s identity that this could create problems for them in the community, in terms of reintegrating. There was that point where the Yazidi Spiritual Committee and the community welcomed the women and girls back, and it was unprecedented, and it was a really remarkable step. It gave the families permission to take the women back, and it gave the women and girls the green light to escape and come back and know that they would be accepted. It didn’t mean that these issues didn’t exist; that even though they said they were accepted back with their honour intact, that didn’t necessarily translate to everyone is not stigmatized. In that context, the journalists kept going to the camps, interviewing survivors, putting these really graphic stories into the press and online, and I was having very interesting conversations with journalists about how this was problematic for the well-being of the survivors themselves, and then for the community at large.

I understood why the Yazidi community wanted these atrocities to be told, it’s very important that the stories are told, but it was the way that the stories were being gathered and reported that just seemed so concerning. So, that’s when I decided in 2016 to partner up with a good friend of mine and sociologist, Dr Johanna Foster, who teaches at Monmouth University. We just decided to do the research. We decided, let’s look at what the women and survivors think. So, we designed the research and carried it out, and that’s what led to the Voices of Yazidi Women paper.

Alannah: Thank you, and I’ll link that for listeners who might want to look it up, because I’ve already told you that it was one of the first things I read before first visiting IDP camps in 2021, and it was incredibly necessary. Of course, these issues are not only found in the media, and I think that’s something we can go on to discuss, but particularly the findings and the suggestions that you both put together in the research are incredibly useful, and it needs to be told. I will link that for those keen to read more.

I wondered also whether you might be able to talk a little bit about the other amazing research that’s come out of these issues, such as The Murad Code and the work of the Dart Center [for Journalism and Trauma], and these are all incredibly useful links for people who might be interested to learn more.

Obviously, people who go and do this work or interact with survivors, they do have a responsibility and an obligation, but it’s also important to explain these things in a less judgmental way. Lots of this advice is very thoughtful. I wonder if you could explain to listeners a little about these documents.

Sherizaan: Sure, and to your point, you’re absolutely right that the issues that we identified with the media were definitely not restricted to that space. The NGOs were also engaging in concerning practices, and they do have clear guidance about Do No Harm and survivor-centred approaches, and then also investigative bodies. So, really, across the spectrum, these survivors were being put on the spot to go into extensive detail about what happened to them, putting them at risk of being re-traumatized. Because the focus was so extreme, and the treatment of the survivors quite egregious, that is what really led to the development – and not just the Yazidi context, you’ve seen this in Myanmar as well, the disproportionate focus on sexual violence – but we’ve seen the development of very useful codes and guidelines.

The Murad Code, named after the survivor and Nobel Prize winner, Nadia Murad, is a global code of conduct that applies to anyone who is documenting conflict-related sexual violence, and really goes into the whole spectrum of what you should be thinking about, how you should be planning for this, informed consent; all of these components. Like I said, it applies to many different actors. The EU Dart Center guidelines were developed by and for journalists and documentary filmmakers, and so it’s really focused on the media. But I think it’s presented in such a plain, clear, easy-to-read way that it’s useful for anyone who is engaging in this work, and I would strongly encourage people to check those out. All of these have been translated into different languages as well, including Ukrainian, given the current conflict. There are others; the UN has developed guidelines, Rutger’s University published the book, “Silence and Omissions,” that provides very sensitive guidance. So, the guidelines are there, the information is there, the question is, are people going to use it?

Alannah: Exactly, which leads quite nicely on to another question, which is tying your work with C4JR a little bit. For listeners who might not know so much about the Coalition for Just Reparations, we have many different working groups, so one of them in particular is the Ethical Engagement Working Group. Sherizaan has been delivering training to members of this group, and is in the process of providing really useful support and advice. I hope you can speak a bit more about it, but to place it in context, the idea is that by training and providing survivors and their community with this advice and guidance and knowledge, you’re empowering the very people who need to know what’s acceptable and what’s not.

Of course, as you were saying before with journalists going into camps, I’ve kind of faced this myself from the other side; you want to tell people’s stories because you think it might change something, or that it’s important to get it out there. But of course, on the other side, survivors feel pressure to share very personal, intrusive things because they think it might help them. It’s very important to set out from the offset that is not a deal, that is not guaranteed, and it’s actually a pretty dangerous assumption to make. What you’re doing with survivors is really incredible and important because they need to know that too.

Sherizaan: In the research, we interviewed 26 women, we never asked anyone if they were survivors, but it was clear from the way that they responded that half of the sample were survivors, and the research led to five key findings. So, the first one is that the women said that they felt pressure to talk to journalists. And this is really important, because they felt pressure from the community, in some cases from their relatives, from managers in the camps, and also by the journalists themselves. So, for example, one survivor said, “I said no at the beginning, but they said this is for your own benefit and one day you will benefit, and this is the only reason I talked to them”. Another finding is that women suffered intense, emotional pain when they talked about their traumatic experiences. They did report breaking down crying, fainting, and insomnia after these interviews; not across the board, but these were some pretty intense experiences for them. It would make them tired, and they also talked about flashbacks. One woman said, “Each time we tell them our stories, we go back to them,” like a flashback meaning they are with ISIS again in their minds.

The third one was that journalists undermined the personal safety of survivors and their relatives. 90 percent of the survivors said it was harmful to disclose their names and their faces or other identifying information. I found that to be remarkable, because if you just type in Yazidi women you will see tons of articles and interviews with their identities exposed. They were also worried that ISIS would retaliate against relatives in captivity, and one of the women we interviewed said ISIS actually did beat her and family members after her relative escaped and went on TV. One of my favourite quotes that I think is so telling, is that a woman said, “Even with my face covered, I did not feel safe. They know everything about me, they can know me from my eyes, even I know them when they are covered.” People need to remember that putting a scarf partially covering someone’s face doesn’t necessarily afford anonymity.

The fourth one was that women reported that, despite the pain that they felt, it was worthwhile to engage with the media. 31 percent of the women reported positive feelings after these interviews, which I think emphasizes the point that these stories are important to tell and when they’re done well, they can leave everyone feeling okay. Feeling empowered, like “I’m trying to help my community, and I’m being given the opportunity to tell my story, but I’m doing it in a way that’s dignified, where I have some control in this situation”. When someone is empathetic and listens to them, it can really help someone feel relieved.

The fifth finding was that, even though the women suffered and struggled in the telling and retelling of their stories, they felt frustrated and angry and betrayed. Because they felt like all of this extensive media attention didn’t really lead to the kind of results that they were hoping for, specifically the return of their relatives in captivity, return to Sinjar with protection and safety and justice. If you look at the situation even today, many people living in camps, it’s not a great situation. You can see why they feel like maybe it really wasn’t worth it.

Alannah: Thank you so much for running through that. There’s an amazing appendix to the research which is also useful for listeners who want to follow up on this. It’s interesting to me that this was published in 2018, six years ago. Do you think things are getting better? I’m conscious that the 10th anniversary is coming up, and I’m imagining more stories. We were talking earlier about local journalism, which is still quite problematic on these issues, although there has been a concerted effort in terms of training and awareness, and people’s faces are now being hidden more often. Social media is another issue, but in terms of local media that’s probably improving slowly. What are your thoughts, as we look ahead to the tenth anniversary? Are you more confident that these women’s stories are being more thoughtfully told?

Sherizaan: I think there has been change because there are people who are sensitive to these issues and who care about ethical storytelling. But I am concerned with the ten-year anniversary and all of the attention on this community, that people will be again going for the sensational stories. One of the problems with the guidelines is that they have no teeth; they’re purely voluntary, and if people are unethical, there are no consequences. My view at this point, and I’ve thought this for some time, is that there has to be a multi-pronged approach. It’s not just about focusing on the media and saying, “You need to do better”. And it’s not just about the journalists – there are editors and all of these people, as you know, behind the scenes who also make important decisions. The survivors need to be empowered to know what their rights are, to know how to advocate for themselves and others; the NGOs need to do their job in terms of advancing and protecting the rights of survivors. You asked about the work with C4JR. Part of it is bringing those guidelines and the checklists that C4JR has already created to light. How do you take these and make them useable and applicable so everyone is on board and aware and on notice that this is what survivors want to see happen. I’m coming up with some recommendations for how survivors, C4JR and NGOs can really assertively get the word out there that, this is what’s okay, and this is what’s not okay, and keep trying to address this issue from different angles.

Alannah: Thank you. I would just add to that, C4JR is very proud because it has these Internal Guidelines on Ethical Engagement with Survivors of SGBV, and a Checklist for Media Involvement, and we try as hard as possible to make that clear and set boundaries. But it’s not uncommon to get messages from journalists trying to be connected with a survivor. It’s a tricky situation to be in when you’re trying to advocate on behalf of a community that it’s very inappropriate to shout about very personal issues. Even you were saying before, in documentation by NGOs or even legal documentation, very many problematic things can occur. Like you’re saying, it seems pretty important to reiterate and encourage survivors that they have agency, and that they can say no to intrusive and inappropriate demands, and create the kind of context in which that’s more permissible. Perhaps you could share a little bit more about the ethical engagement training with C4JR, and general guidance and how to encourage?

Sherizaan: It’s still actually under development, I’m putting it all together right now, but I did have a consultation recently with survivors, and I’ve had several consultations with survivors since the Voices paper was published. I’m always hearing the same thing about their frustration with the way that they’re treated at conferences, at commemorative events, the way you see survivors when they come back from captivity, and the camera is on them, and they have no opportunity to consent or understand what’s going on. It’s very interesting because, again, I never say that these stories shouldn’t be told, and I think sometimes people misunderstand me. I’m just saying they should be done ethically.

Like you said, survivors have agency; they have autonomy, and they should be empowered. But they need to have the information to help them decide what they want to do, and they need the space to decide what stories they want to tell, which might be different from what the media wants to tell. I know the community wants the story to stay in the media, of course they don’t want it to be forgotten. So how do you tell that story in a way that doesn’t cause harm? I think that’s the key. Part of what I’m trying to put together for C4JR is, okay, those requests come in, how do you manage that? How do you engage with the survivor community? Let them know it’s totally voluntary, but if they’re interested, then provide them with the support that they need to go out there and feel confident about what they’re doing.

Alannah: Great, that’s really useful, thank you. And we’re grateful for that work. I think if it’s okay, we can move on to talk a little bit more specifically about the Yazidi Survivors Law, which you’ve also been very much involved in. I have a few questions on how the YSL has developed over recent years, and perhaps the one that’s most relevant to this conversation is the survivor-centred aspect of the law. Just for listeners who may not be fully aware, the Yazidi Survivors Law is such a comprehensive piece of legislation because it goes beyond mere financial compensation to include land, housing, employment, education, memorization, genocide recognition, searching for the missing, and criminal justice. Bylaws even speak about updating school curricula to properly reflect ISIS atrocities. It is far more of a transitional justice framework than just an administrative reparations program.

But, here is the thing. What about the process? In our experience, outreach, application, review of application and the process of the actual delivery of benefits is at least equally important as the outcome, such as the financial reparations themselves. In other words, how can the process be made more survivor-centred, trauma-informed and in line with tenants that guide ethical engagement with survivors?

Sherizaan: It’s been really a great opportunity for me to work with IOM on this process, for more than two years now. People often throw out the term survivor-centred. I don’t think they always quite know how it applies in practice. In the context of applying for reparations, there are several components that I think are really critical to emphasize. One is that the decision to apply, the decision about what information to provide, or what evidence to submit, it all really needs to be with the survivor. They may or may not feel comfortable providing certain information, and it may affect their application, but they need to know all of that information to help them make an informed decision.

Reparations, in this context, really need to be accessible, they need to be prompt, they need to not burden the survivors; these are all really key aspects of a survivor-centred approach to reparations of sexual violence. And that’s why an administrative program, allows for a survivor-centred approach. Because all of those conditions can be met, in addition to a very important element which is confidentiality and Do No Harm. A lot of these elements were in the design of the YSL and the bylaws, but then that changed later when the requirement was added; the Extra-Legal Requirement that all survivors go through the criminal investigation process as the precondition of qualifying for reparations. That really took things in a different direction.

Alannah: I was going to ask whether this new Extra-Legal Requirement [for survivors to submit a criminal complaint and annex investigative paper to their YSL application, quite unexpectedly introduced by the Committee]. How badly has this contaminated the application and review process? In the sense that, despite consistent efforts by civil society actors and international organizations, C4JR and all of our members were, by and large, mostly for removing this requirement, it doesn’t look very likely that that will happen. Can we still speak of the Yazidi Survivors Law as an advanced and ground-breaking law with this quite burdensome criminal complaint aspect on survivors?

Sherizaan: Your initial question on how important the process is relative to the outcome, I think they are both equally important. Let me just say this, this is the routine way that things are done in Iraq. The way that the law is currently being applied is consistent with bureaucratic and investigatory procedures that exist, for example under Law 20 (Compensation for Housing, Land and Property). What we were hoping for was a departure from the norm to make this survivor-centred, but I can see how such a significant change like that is challenging. Maybe we were unrealistic in thinking that could happen. Initially, the Directorate had endorsed it, and the people who had drafted the law and the bylaws agreed that it shouldn’t be included, but I think once it started being implemented, people reverted back to what they were familiar with.

There’s this feeling that by going through that investigation process, there is sort of another buffer to confirm that someone is really a survivor, so it shares some of the burden with the Committee in the decision-making process, but what it’s done is it’s shifted the burden also to the survivor. Initially, survivors should have been able to apply remotely using the online portal, and that was really included also for survivors outside of Iraq, who shouldn’t have to travel back to the country to go through this process. But once the criminal investigation requirement was put in place, it meant that everyone had to be physically present in Iraq, and then had to go back to their place of origin, where they were originally abducted and separated from their families and file the criminal complaint with the police and then go through that process before their application for reparations would be considered. So that’s quite burdensome because now you’re adding additional interviews, you’re adding a lot of travel, it’s expensive, it’s emotionally difficult, people have to go not only to their place of origin, but Mosul where many were held in captivity.

So, now you’re talking about a system that is looking less and less survivor-centered and more burdensome for those who have endured incredibly traumatic experiences already. You can imagine how difficult that is for people to then go through that process again, at their own expense and often without significant support. I know that there’s an active civil society, but I don’t think that I have really seen organizations take survivors and represent them from the beginning, from the time of the application, all the way through the process, supporting them with transportation, being present, when they’re being interviewed, you know, full representation. I just think that they don’t have the resources, and they don’t have the funding to provide that level of support. Survivors are largely on their own once they go out there and start going through this process.

Alannah: That’s such a good point. I have spoken to a few NGOs, members of C4JR, who provide legal advice, and they say how very often they have to use other programs such as emergency cash assistance programs, which come from a completely different funding stream, to support them to now travel back to areas of origin. Obviously the Directorate is a Nineveh, and so you have this quite burdensome process like you’re saying. C4JR has been engaged in conversations about opening offices in areas where survivors are based and, for various reasons, that’s not happening at the moment. So, clearly the whole process could be improved a lot.

You mentioned also about survivors returning in order to apply, and that’s also something that C4JR has been looking into more recently, having a few consultations with members abroad. Although well over a thousand survivors are now receiving reparations in Iraq, which is brilliant, it’s quite unclear precisely the numbers of eligible survivors that are still to apply or receive support, that’s one of the problems, but there are definitely many more survivors abroad, specifically in Germany, and also we know many in Canada and Australia, who haven’t yet applied and are eligible. And yet the process of helping them to apply is just really complicated, and there are cases and examples of people flying back from Canada in order to get this sorted. Things aren’t particularly aligning in terms of all the different support that’s out there from different organizations. Which is all a long-winded way of saying, everything you said there makes total sense on the ground.

Sherizaan: It’s not just the investigation process; Iraqi government organizations tend to operate in person. Procedures are generally not done online. If you want to pick up your letter from the Genocide Office in Duhok, you have to go in person. If you come from abroad, you probably need to give yourself a minimum of two months in-country to get everything done. Not everyone can afford the ticket or the time that it takes to do that.

Alannah: Thank you very much, and in light of all of that and considering what we’ve discussed today, I wonder if looking forward to the continued implementation of the Yazidi Survivors Law, what you think civil society actors, activists, and government should really be focusing on and working towards as we continue to support this process, particularly in light of everything you’ve spoken so importantly and eloquently about ethical engagement and keeping survivors at the very centre of what is obviously a very complex and traumatic process, too.

Sherizaan: I think the survivors need to be at the centre of the process; their needs, and their concerns, and they need to be treated with dignity and respect. A lot has been accomplished; more than 1,600 applications have been approved. That’s in less than two years, so that is no small feat. Just the salary payments alone are really transformative for people who don’t have access to employment or livelihoods, may have lost out on their education, and came back to broken families. Many women lost their husbands. This is significant. And the goal, of course, is to ensure that everyone who qualifies has access to these benefits because we know that they’re so helpful.

Looking ahead, as this law continues to be implemented, as the government and civil society continue to try to improve the way that support is being provided to survivors, I think we need to really continue to keep this law and the reparations and transitional justice program top of the agenda. Because we don’t want to forget that these people are still struggling a lot and that this genocide is not over, and they really need the support.

I would start with the donors perhaps, because I know there are other countries that are very invested in seeing this law successful. I would really encourage donors to support the representation of survivors, so that they have people advocating for their rights all the way through the process, including on appeal. If your case is not approved, you can appeal to the committee and then you can appeal to the Court of First Instance. You can’t really go through that final step if you don’t have a lawyer, but if you do have a lawyer at the beginning of the process, then I think the chance of you being successful increases exponentially, and then the same for survivors who are overseas.

My main recommendation, of course, would be to remove the investigation requirements and not put the burden on the survivors to provide additional evidence, but to put the burden back on the government to set up clear screening procedures from a survivor-centred approach and a trauma-informed approach, to review the evidence. And often the extensive evidence, we haven’t even mentioned how many testimonies have been already documented from survivors, over the last ten years. Then civil society, to advocate for the resources that they need to make sure that the survivors are supported throughout the entire process, covering a lot of these expenses. It’s not cheap to travel from camps to Sinjar, back and forth, multiple times. This is very expensive for people who have no jobs.

So, I think civil society should continue to do outreach, raise awareness, identify those who have had difficulty applying, and support them, and then to continue to support the government. If these investigation papers stay in place, then I think it’s really important to make sure that the police and the investigative judges, and everyone involved in engaging with survivors, is trained on how to do proper interviews, provides private space, ensures that women are part of those interviews, particularly with women. So even if you don’t have women working as investigative judges and police, you have women staff in these offices who could be present to help women feel more comfortable, making sure that these things are done according to best practices, but also within the Directorate. For example, the Survivor’s Directorate also helps survivors submit applications. It’s really important that the people who are doing that are also trained and mentored on an ongoing basis, and that these interviews and these cases are put together privately in confidential spaces, because confidentiality is built into the law. It’s really important for people to come forward and feel safe and feel comfortable and feel like their information is not going to be shared publicly without their permission.

Alannah: Thank you so much, Sherizaan, for your time, expertise, and care, and incredible knowledge on this subject. I hope listeners have taken something from this conversation, and I’ll make sure to link everything that we mentioned. Thank you, thank you very much.

Sherizaan: Thank you so much for having me.

Mentioned Links:

- Foster, Johanna, & Minwalla, Sherizaan. (2018). Voices of Yazidi women: Perceptions of journalistic practices in the reporting on ISIS sexual violence. Women’s Studies International Forum, 67, 53–64: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.01.007 (and Appendix: “Select guidelines for ethical reporting on sexual violence in conflict zones”);

- The Murad Code project is a global consultative initiative aimed at building and supporting a community of better practice for, with and concerning survivors of systematic and conflict-related sexual violence (“SCRSV”). Its key objective is to respect and support survivors’ rights and to ensure work with survivors to investigate, document and record their experiences is safe, ethical and effective in upholding their human rights: https://www.muradcode.com;

- Dart Centre Europe, Reporting on Sexual Violence in Conflict: https://www.coveringcrsv.org;

- Cosette, Thompson. (2021). Silence and Omissions: A Media Guide for Covering Gender-Based Violence. Rutger’s University: https://gbvjournalism.org/book/silence-and-omissions-a-media-guide-for-covering-gender-based-violence;

- C4JR Internal Guidelines on Ethical Engagement with Survivors of SGBV: https://c4jr.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-Internal-Guidelines-on-Ethical-Engagement-with-Survivors-of-Sexual-and-Gender-Based-Violence-ENG-1.pdf;

- C4JR Checklist for Media Involvement: https://c4jr.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/B-Checklist-for-Media-Involvement-ENG-1.pdf;

- C4JR Asks Iraqi Officials to Put the Well-being of Survivors First: https://c4jr.org/0604202327330.

The Coalition for Just Reparations (C4JR) is an alliance of Iraqi CSOs, helping survivors of the ISIS conflict in Iraq realise their right to reparations, as we seek the full implementation of the 2021 Yazidi Survivors Law (YSL); a comprehensive state-funded reparation program providing reparations if you are a member of one of the following groups: Adult and minor female survivors of ISIS captivity from the Yazidi, Shabak, Christian or Turkmen communities, male Yazidis who were abducted by ISIS when they were under the age of 18 at the time of abduction, and all persons from the Yazidi, Shabak, Christian or Turkmen communities whom ISIS abducted and personally survived a specific incident of ISIS mass killing. Applications are made to the General Directorate for Survivors’ Affairs, a government body recently established in Iraq under the auspices of the federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs and verified by the eight member commitee consisting of representatives of different Iraqi institutions.