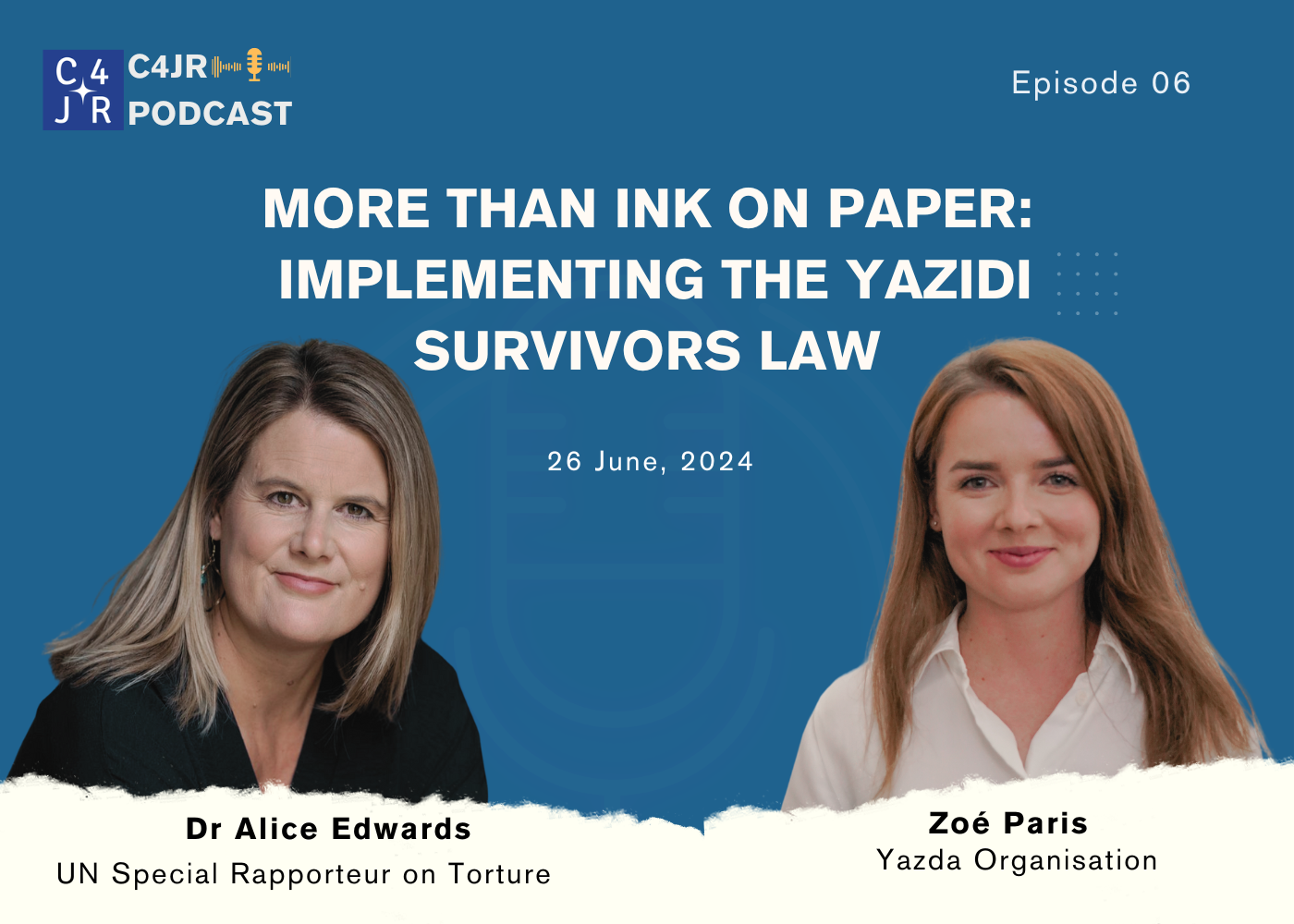

Implementing the Yazidi Survivors Law: Watch and Listen to C4JR in conversation with Dr. Alice Edwards, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, on Spotify and Youtube.

Episode Description:

In this episode of the YSL podcast, published on the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, Zoé Paris, a jurist in international law with Yazda, interviews Dr. Alice Jill Edwards, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

Yazda is a community-led organization promoting accountability and justice for the genocide committed by the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (“ISIL”) against the Yazidi community and other groups. Since its creation in August 2014, Yazda provides a wide range of services to survivors of the genocide and advocates for a comprehensive transitional justice process in Iraq, with a focus on criminal accountability, access to reparations, and truth. Dr. Edwards discusses her extensive work in human rights, refugee law, and criminal justice, highlighting her focus on issues affecting victims of war and violence, especially women and girls. She elaborates on her visit to Iraq, her participation in a conference by the Coalition for Just Reparations and the Jiyan Foundation for Human Rights, and the importance of framing rehabilitation as a right under international law.

The conversation delves into Dr. Edwards’ forthcoming report on sexual violence as a form of torture during armed conflict. The Special Rapporteur explains the significance of framing sexual violence as a form of torture when committed within places where persons are deprived of their liberty or anywhere an official has control over a person, notably to ensure survivors receive appropriate justice.

The episode also covers the challenges of implementing Iraq’s pioneering Yazidi Survivors Law, which provides comprehensive reparations for survivors of ISIS crimes. Dr. Edwards shares her impressions of Iraq, praising the commitment of civil society actors and the engagement of survivors in rehabilitation programmes. This episode offers insightful perspectives on transitional justice, rehabilitation, and the ongoing efforts to support survivors of conflict-related atrocities.

Transcript:

Zoé Paris: Hello, my name is Zoé Paris. I’m a jurist in international law and I work with Yazda Organisation, which was created a few weeks after the beginning of the genocide committed by ISIS against Yazidi and other ethnic and religious minority groups in Iraq to support and provide services to these communities, with a particular emphasis on transitional justice.

Yazda is a member organisation of the Coalition for Just Reparations (C4JR), and we are really happy to have Dr. Alice Jill Edwards with us today. She is a UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. Thank you so much, Dr. Alice, for being with us today.

Thank you so much for visiting Iraq and taking the time to speak with civil society organisations and survivor groups. It’s really an honour to have you here. To begin, I’d like to introduce you. You are an international lawyer with extensive expertise in human rights, refugee law, and criminal justice. You have been working on the issue of torture since the 1990s, through field and academic work, focusing particularly on issues affecting victims of war and violence, in particular women and girls. You have also worked on the subject of the feminisation of torture under international law.

You have advised governments, international and national institutions, and civil society organisations. You’ve worked in Geneva, Bosnia, Morocco, and Rwanda, and have written more than 50 publications. More recently, you were appointed as the seventh and first female United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture. Thank you again, and it’s an honour to have you.

Let’s start by discussing your visit to Iraq. The Coalition for Just Reparations and the Jiyan Foundation invited you to participate in a conference focused on a guide that was developed to monitor the right to rehabilitation for survivors of ISIS, using human rights indicators. You were a speaker at that conference. Could you discuss the question of rehabilitation and framing it as a right under international law, which is a relatively new approach? In state responses to torture, in the past, the focus was, first and foremost, on the question of criminal accountability, then access to reparation, and in particular on financial compensation. Rehabilitation as a right remains very elusive. Why is that?

Dr. Alice Edwards: Thank you, Zoé, for having me on the podcast. It’s great to be in Iraq. I visited Duhok and Erbil and met with some survivors of ISIS, learning about their experiences, and the terrible history of the most recent period in Iraq. You asked about rehabilitation. In fact, Article 14 of the UN Convention Against Torture, which is an instrument from the 1980s, incorporated the right to rehabilitation alongside the right to compensation within that instrument. So it’s not a new right at all.

What has developed over time, is that states are now putting it on a legal footing, so they are now enacting domestic legislation to provide individuals and communities with the right to rehabilitation. I would also say, that there’s been a shift in understanding rehabilitation more holistically. In the 1980s, when the convention was being developed, the focus was on survivors of dictatorships in Latin America who had been subjected to terrible forms of torture, false disappearances, and other violations.

What developed was essentially psychosocial rehabilitation; the psychological support needed. Some former Holocaust Survivors were also involved in developing this stream of psychological and psychiatric support for refugees who had fled from those dictatorships. These days, we talk about rehabilitation – I think this is the change – more holistically. It’s not only about the psychological support, which is absolutely crucial; it’s also about medical support, recovery from one’s injuries, and it’s also about legal, economic and other support that people need in order to be able to make a full recovery and to reintegrate into their families, into their communities, and that society as a whole can recover.

Zoé: Thank you so much for this. One of the reasons for your visit to Iraq is your work on a thematic report on sexual violence as a form of torture during armed conflict. Part of this report will be focused on remedies and rehabilitation for survivors. Can you tell us more about this report, and can you explain to us the difference between sexual violence as a form of torture under international law, and sexual violence as a crime in itself? Why did you choose to address specifically wartime sexual torture?

Dr. Edwards: I’m really happy to be able to talk to you about my forthcoming report, which I’ll be delivering to the General Assembly in October this year. Every year I write two reports as the Special Rapporteur on Torture; a role appointed by UN member states in order to advise them on issues, current topics and trends related to the prohibition and prevention of torture. This is in fact, a follow-up report. I wrote a report on the duty to investigate and prosecute crimes of torture a year ago, and this new version will focus more concretely on the more specific crime of sexual torture.

We know that torture is both psychological and physical. It may be one, it may be the other, but ultimately normally it’s both; people may have physical injuries from the torture, but of course it carries great haunting and great psychological trauma. Likewise, psychological forms of torture often lead to physiological symptoms. In the case of sexual torture, it’s almost impossible to separate out those two.

I also think, what I’m seeing across the world, with deep regret, is that sexual torture is still being used as a means of warfare; of perpetrating egregious forms of torture and within that context also sexual forms of torture. It is one of the most extreme forms of humiliation and cruelty.

The reason for using the frame of torture, you asked about the difference with conflict-related sexual violence and sexual torture. The definitions are different, but as this report is developing, what I’m really seeing is that for survivors, being able to frame things as torture allows them to speak more fully about the full range of experiences that they may have had, that they get to talk to the multiple violations that occurred and that there is not this pre-occupational pigeonholing with a specific form of torture.

What we know from almost all forms of torture is that it’s multiple violations, together. For some survivors, it’s a helpful framework in which they can talk broadly about what’s happened to them and the frame of torture may be applicable, including sexual torture.

The second thing to say is that, from a justice perspective, the legalities of calling something torture as opposed to conflict-related sexual violence – which is more a policy term that was developed for an agenda following the resolution 1325 – to actually give focus to what we’re discussing today, and it has had a big effect in that regard. However, as a legal matter and as a justice matter there are advantages to calling sexual torture and naming it correctly as torture within the continuum of torture.

I’ll mention a few. First of all, torture is absolutely prohibited under international law; that is accepted by all states. When sexual violations are framed as torture, they are absolutely prohibited under international law. There are no defences of command responsibility. There are no statutes of limitations, which means that at no point is the government able to say, that one can’t raise a claim of torture. There are no immunities or amnesties that may be imposed, that otherwise might be imposed for other types of crimes.

I do think both from a rehabilitation perspective for survivors, but also from a justice perspective, which can be part of their rehabilitation but also a standalone area, using the torture frame can be very helpful. I think that’s one of the strongest reasons; there’s no shame in torture.

You get to be able to claim that you’re a victim or a survivor of torture, and there is no shame in that. Whereas we do know, in most societies, there are shames and stigmas that attach regrettably to survivors of sexual violence. I think it also allows the dignity for people and survivors, whether men or women or children, to be able to speak more freely about their experiences and to have them framed in this way.

Zoé: That’s extremely interesting, and the part on accountability, and being able to prosecute more easily on the basis of torture is really interesting. Given that you are currently visiting Iraq, there is a subject that I would like to ask you about, and given that you’ve discussed with survivors of crimes committed by ISIS, including sexual violence. The Yazidi Survivors Law was passed by the Iraqi Parliament, on March 1st 2021, and it established an administrative reparation mechanism for four religious and ethnic groups in Iraq, which are the Shabak, Christian, Turkmen and Yazidis. This is the first reparation programme in the Middle East, and one of the few in the world which focuses on providing reparations and comprehensive sets of reparations to survivors of conflict-related sexual violence.

The law explicitly refers to several forms of conflict-related sexual violence, including rape, sexual slavery, forced marriage, forced pregnancy and forced abortion. It mandates both individual and collective reparation measures, but also material and symbolic reparations, including rehabilitation, monthly financial compensation, access to land, education, and employment. Generally speaking, and drawing from your experience from other post-conflict settings, what are the challenges that can happen when implementing such a comprehensive reparation program?

Dr. Alice Edwards: First of all, let me say that this law is pioneering for this region, as you mentioned. It’s a very good first step towards other legal rights, around the framework of torture, but also genocide and other atrocity crimes. Challenges that I’ve seen elsewhere in terms of similar laws, or access to rehabilitation that has a legal basis first of all is, how inclusive is the law? Do people feel as though they are included? Are there problems with groups being left out? In many ways, while there are certain victims of especially ISIS crimes, there is also the wider community and various different groups, including men and boys and children, who also need to be incorporated into any rehabilitation programmes and laws.

The second I’d say, is making sure that people are aware that the law exists and how they are able to exercise their rights. The third I would say, is about accessibility. Whether people know how to get access, where they apply, is the place where they apply safe? Do they feel that they have to expose themselves, or has there been a measure of confidentiality ensured throughout the process? Also very important that the resources and expertise of those who are not only receiving the applications, but also then delivering on this rather large-scale effort to provide rehabilitation for victims and survivors. The resources and the expertise of the government and other service providers need to be ready and well-equipped. I would say, throughout all of that process, ensuring that survivors of ISIS crimes are not re-traumatised in this process; that this is survivor-led. I understand that there were lots of consultations with survivors in this law, but likewise those consultations need to continue through the law’s implementation.

Zoé: Thank you very much and all of this is very relevant to the Yazidi Survivors Law, and to what we’re seeing in Iraq, in terms of implementation of the law. We conducted an assessment at Yazda and found that many survivors knew about the law’s financial compensation, but not about the other reparation measures within the law. As we discussed, there has been a lot if issues related to access. My final question is, are there any impressions that you would like to share with us on the days that you spent in Iraq?

Dr. Edwards: I’m glad you gave me this opportunity Zoé, to do the podcast, but also to say a few words at the end. I’ve been really blown away by the level of commitment of the civil society actors that I’ve met, and the survivors’ engagement in those organisations; being members of staff, being clients, engaging in networks. I also think this kind of coordination that the NGOs and others have through the Coalition for Just Reparations – in this big poster beside us – shows how many people and organisations are involved. I have also been impressed by the wish and desire to continually improve, whether that’s psychosocial support, physio, all of the services, and how there’s this kind of continuous learning and training and sharing. I think if all of these people were in charge of the rehabilitation programme that’s being planned, I think the survivors are in very good hands. Congratulations.

Zoé: Thank you very much, Dr. Alice Jill Edwards. Thank you again for taking the time to come to Iraq. It meant a lot to civil society organisations and survivor groups in Iraq. When we asked them if they were interested in meeting you, they all said, of course; it’s so important for us to be able to talk about this and in particular with the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture. Thank you for your time and for the podcast.

The Coalition for Just Reparations (C4JR) is an alliance of Iraqi CSOs, helping survivors of the ISIS conflict in Iraq realise their right to reparations, as we seek the full implementation of the 2021 Yazidi Survivors Law (YSL); a comprehensive state-funded reparation programme providing reparations if you are a member of one of the following groups: Adult and minor female survivors of ISIS captivity from the Yazidi, Shabak, Christian or Turkmen communities, male Yazidis who were abducted by ISIS when they were under the age of 18 at the time of abduction, and all persons from the Yazidi, Shabak, Christian or Turkmen communities whom ISIS abducted and personally survived a specific incident of ISIS mass killing. Applications are made to the General Directorate for Survivors’ Affairs, a government body recently established in Iraq under the auspices of the federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs and verified by the eight member committee consisting of representatives of different Iraqi institutions.